A recipe for brainstorming user stories

Given below is a possible recipe you can take when using user stories for early stages of requirement gathering.

Step 0: Clear your mind of preconceived product ideas

Even if you already have some idea of what your product will look/behave like in the end, clear your mind of those ideas. The product is the solution. At this point, we are still at the stage of figuring out the problem (i.e., user requirements). Let's try to get from the problem to the solution in a systematic way, one step at a time.

Step 1: Define the target user as a persona:

Decide your target user's profile (e.g. a student, office worker, programmer, salesperson) and work patterns (e.g. Does he work in groups or alone? Does he share his computer with others?). A clear understanding of the target user will help when deciding the importance of a user story. You can even narrow it down to a persona. Here is an example:

Jean is a university student studying in a non-IT field. She interacts with a lot of people due to her involvement in university clubs/societies. ...

Step 2: Define the problem scope:

Decide the exact problem you are going to solve for the target user. It is also useful to specify what related problems it will not solve so that the exact scope is clear.

ProductX helps Jean keep track of all her school contacts. It does not cover communicating with contacts.

Step 3: List scenarios to form a narrative:

Think of the various scenarios your target user is likely to go through as she uses your app. Following a chronological sequence as if you are telling a story might be helpful.

A. First use:

- Jean gets to know about ProductX. She downloads it and launches it to check out what it can do.

- After playing around with the product for a bit, Jean wants to start using it for real.

- ...

B. Second use: (Jean is still a beginner)

- Jean launches ProductX. She wants to find ...

- ...

C. 10th use: (Jean is a little bit familiar with the app)

- ...

D. 100th use: (Jean is an expert user)

- Jean launches the app and does ... and ... followed by ... as per her usual habit.

- Jean feels some of the data in the app are no longer needed. She wants to get rid of them to reduce clutter.

More examples that might apply to some products:

- Jean uses the app at the start of the day to ...

- Jean uses the app before going to sleep to ...

- Jean hasn't used the app for a while because she was on a three-month training programme. She is now back at work and wants to resume her daily use of the app.

- Jean moves to another company. Some of her clients come with her but some don't.

- Jean starts freelancing in her spare time. She wants to keep her freelancing clients separate from her other clients.

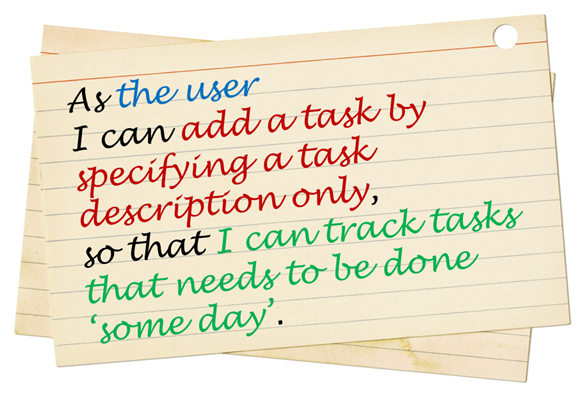

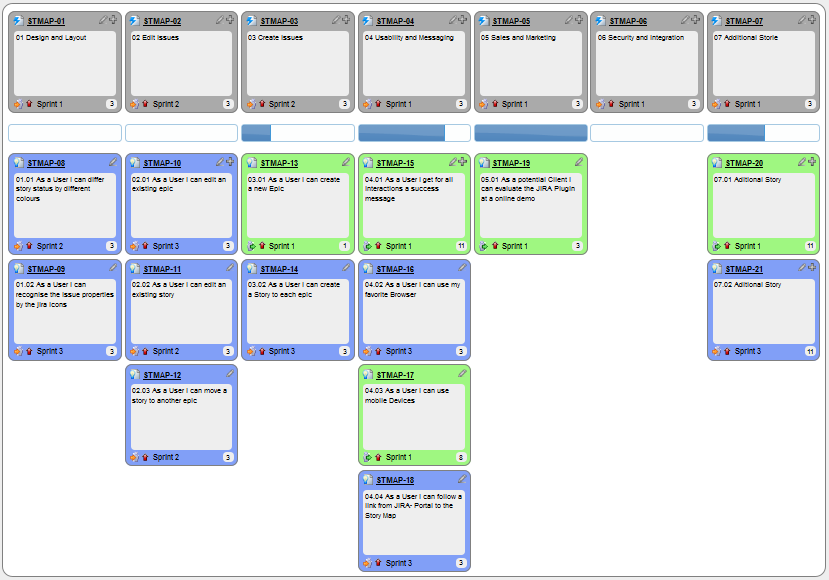

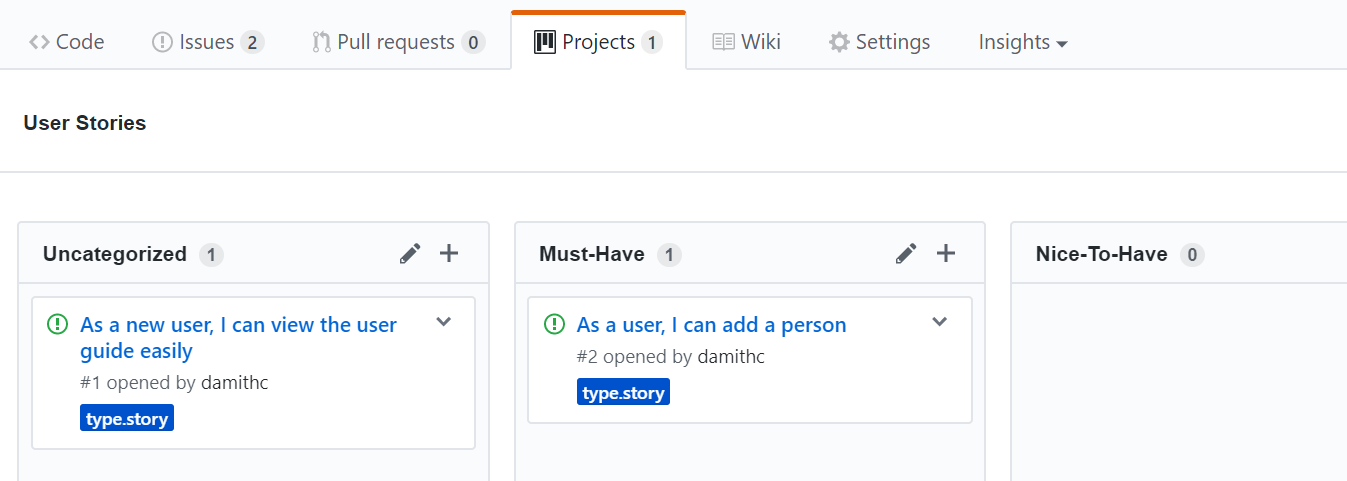

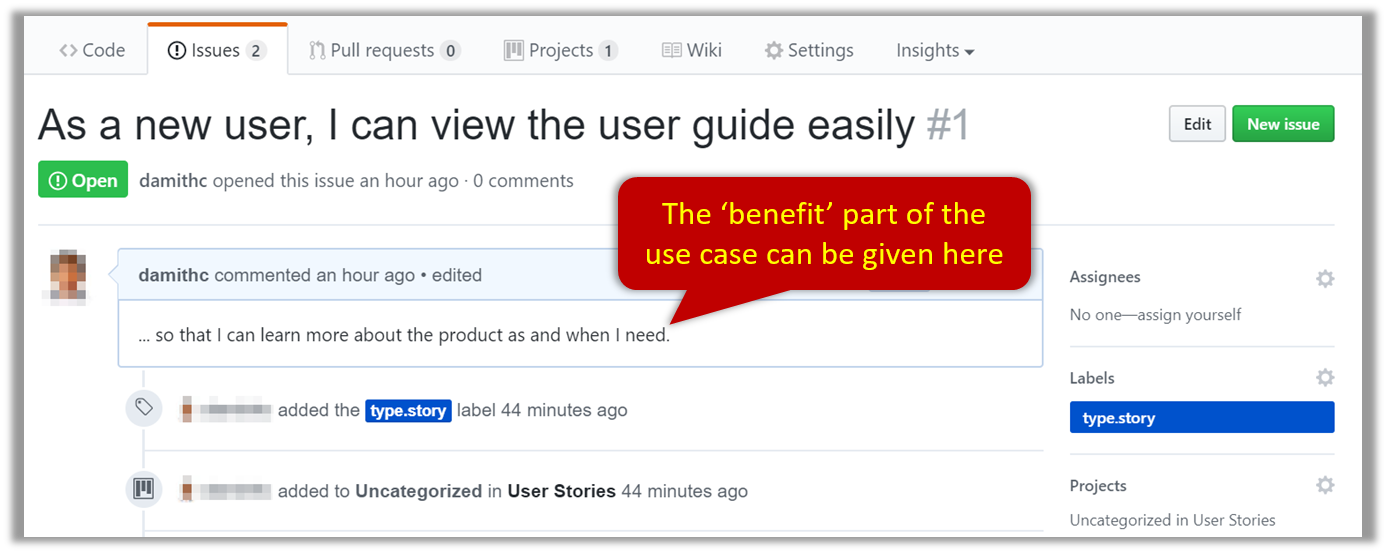

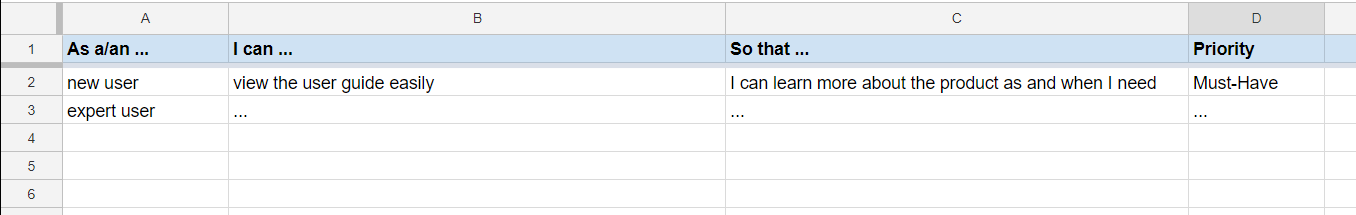

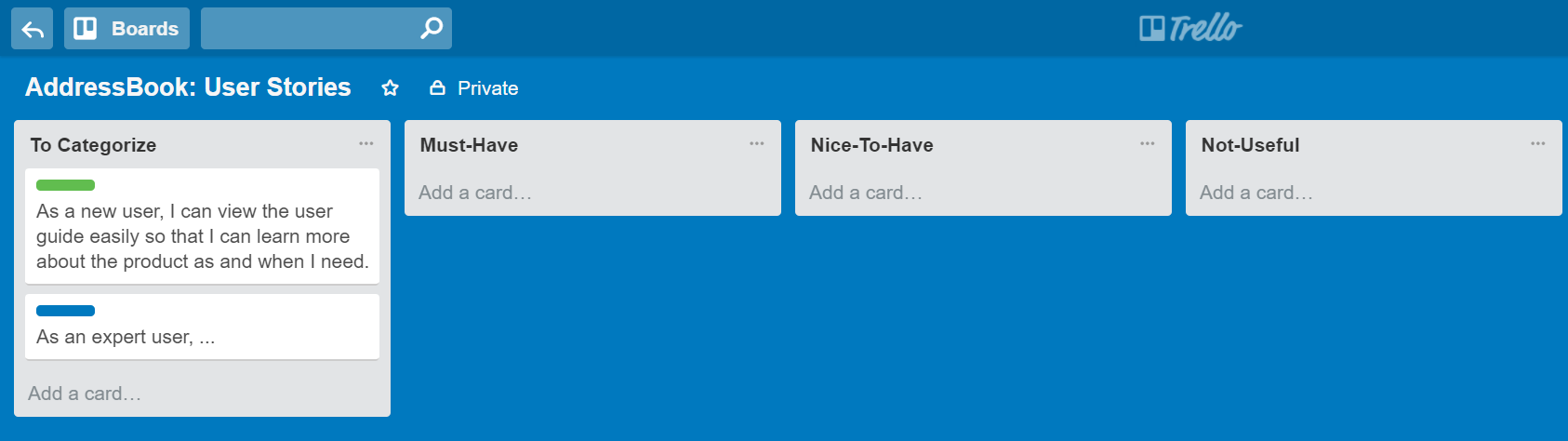

Step 4: List the user stories to support the scenarios:

Based on the scenarios, decide on the user stories you need to support. For example, based on the scenario 'A. First use', you might have user stories such as these:

- As a potential user exploring the app, I can see the app populated with sample data, so that I can easily see how the app will look like when it is in use.

- As a user ready to start using the app, I can purge all current data, so that I can get rid of sample/experimental data I used for exploring the app.

To give another example, based on the scenario 'D. 100th use', you might have user stories such as these:

- As an expert user, I can create shortcuts for tasks, so that I can save time on frequently performed tasks.

- As a long-time user, I can archive/hide unused data, so that I am not distracted by irrelevant data.

Do not 'evaluate' the value of user stories while brainstorming. Reason: an important aspect of brainstorming is not judging the ideas generated.

Other tips:

- Don't be too hasty to discard 'unusual' user stories:

Those might make your product unique and stand out from the rest, at least for the target users.

- Don't go into too much details:

For example, consider this user story: As a user, I want to see a list of tasks that needs my attention most at the present time, so that I pay attention to them first.

When discussing this user story, don't worry about what tasks should be considered needs my attention most at the present time. Those details can be worked out later.

- Don't be biased by preconceived product ideas:

When you are at the stage of identifying user needs, clear your mind of ideas you have about what your end product will look like. That is, don't try to reverse-engineer a preconceived product idea into user stories.

- Don't discuss implementation details or whether you are actually going to implement it:

When gathering requirements, your decision is whether the user's need is important enough for you to want to fulfil it. Implementation details can be discussed later. If a user story turns out to be too difficult to implement later, you can always omit it from the implementation plan.